By Mia Foreman, First 5 LA Program Development Officer

More than 5 million children in the U.S. have had a parent who lived with them go to jail or prison. That’s one in 28 kids, compared with one in 125 about 30 years ago. This proportion is higher among black, poor, and rural children and is more than likely an underestimate since it does not include children with a non-residential parent who is incarcerated. The majority of parents incarcerated are fathers, with 1.1 million serving time in 2010.

Seeing a parent arrested and experiencing a parent serving time in jail or prison is recognized by the ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study as a significant factor for experiencing trauma. Children end up feeling separated from their parent, which can cause feelings of abandonment, shame, grief and guilt. ACEs can lead to a myriad of negative emotional, social and physical health consequences in a child’s youth and well into adulthood.

These are just a few of the daunting facts presented during the panel session, “How Incarceration Affects Fathers in Parenting”, presented June 17 at the 9th Annual Fatherhood Solution Conference presented by Children’s Institute, Inc. and co-sponsored by First 5 LA.

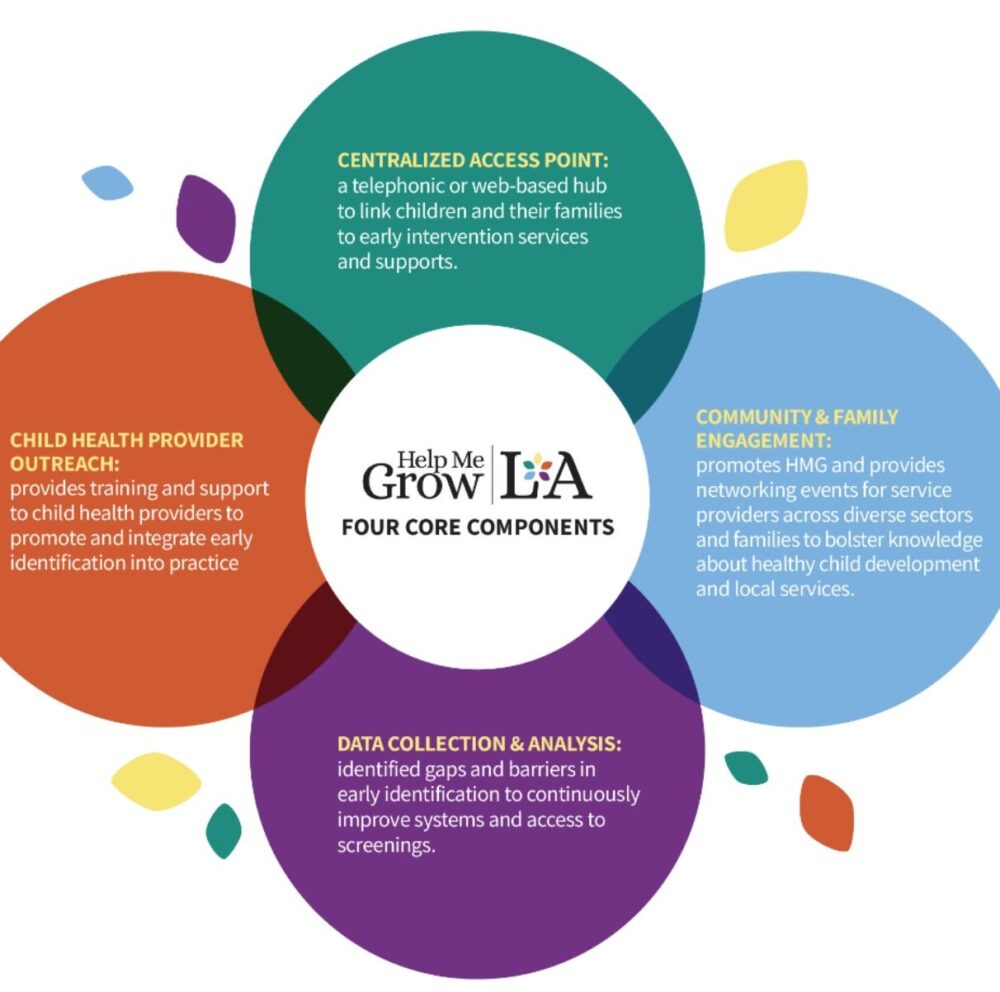

To help combat ACEs, First 5 LA is investing in workforce development training in Parent-Child Interactive Therapy (PCIT) and, as part of its emphasis on trauma-informed care, is partnering with Los Angeles County agencies, foundations and other key stakeholders to determine how the county can become a model for identifying and addressing trauma in children and families in a systematic way.

“The reality is that despite what the incarcerated individual has done, they still have children who need their parents” – Alan-Michael Graves

The panel session on incarceration and parenthood provided a forum to hear the experiences of three fathers who have served time and one child sharing how this impacted their relationship with their children. The session included moderator Donald “Bo” Hulen and panelists Ernest Melendrez, Dorian Esters and Martin Sosa – all of whom have been previously incarcerated and now work at Friends Outside in Los Angeles County.

Alan-Michael Graves, Director of Project Fatherhood with Children’s Institute, Inc., said it was critical that this workshop be part of the conference to highlight the need to work with families of incarcerated parents.

“The reality is that despite what the incarcerated individual has done, they still have children who need their parents,” Graves explained. “However limited the capacity is due to the incarceration, we know that their involvement is essential and can improve the outcomes of those children.”

If the father is incarcerated and contributed financially to his family, the family suffers greatly due to loss of wages, Hulen said. Ninety-one percent of fathers provided some sort of income to the family before being incarcerated.

The challenges do not end once the father is released from the criminal justice system, Hulen added. Re-establishing bonds with the child once the father is out can be difficult due to the mother preventing reconnection due to shame of the situation, the father unable to find housing and employment, and the inability to mentally deal with the trauma of the situation in order to take care of his child.

There is also a general attitude that incarcerated fathers do not play as important role as mothers when raising their children, one panelist noted. Numerous times the father is not notified of court dates or is not visited. When the father gets out of prison, the desire to connect with the family can be severely severed.

“If the father is incarcerated and contributed financially to his family, the family suffers greatly due to loss of wages” – Donald Hulen

For all three fathers, the impact was significant creating spiritual, financial, and emotional trauma including separation anxiety. There was dual traumatization if the father was in prison and the mother was dealing with issues such as drug addiction. The child of one of the panelists shared that having his father in prison twice led to bouts of depression and anger due to his life changing drastically after his father was incarcerated.

Incarceration caused the breakdown of marriages, relationships and overall trust issues among the family. Many times the mother is left struggling to make ends meet which means not much time is spent with her children since she is working multiple jobs.

When children are left to raise themselves, the cycle can easily repeat itself. One panelist mentioned that his child had followed his footsteps in his involvement with the prison system.

When asked what policy changes would support incarcerated fathers, the panel mentioned more funding for housing for fathers after they leave prison so they have a place to welcome their child. Estes also requested complete wraparound services for re-entry fathers and for prisons and jails to connect fathers leaving the system with these resources before they finish their time.

Last but not least, the panelists asked for society to change their opinion of incarcerated fathers so they are no longer seen as fathers who do not care about their children or want to be in their lives. The opposite is true, yet they are unable to do so because of policies in place that prevents them from participating in their children’s lives.