October 28, 2021 | 6 Minute Read

After the pandemic hit in March 2020, the early learning center in Santa Monica where Lizbeth Rivera worked as an associate teacher temporarily closed its doors. When it reopened months later, more than half of its children did not return.

Rivera, a 15-year veteran early educator, watched as her hours were cut. Over the next several months, they dropped from 40 hours a week to 12.

Then eight hours.

Then two.

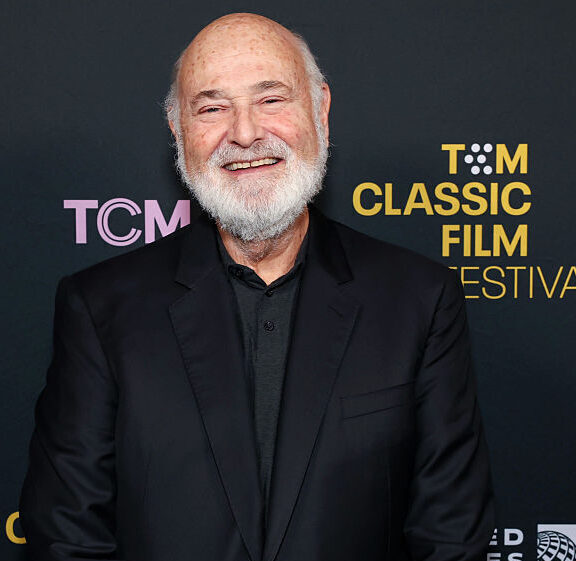

Lizbeth Rivera

“I struggled a lot,” said Rivera, a single mom of two children who lives in Gardena. “I was going to people’s homes and doing facials for $20. I started selling my clothes on Instagram.”

As the economy reopens from the pandemic and people return to work, the need for early care and education (ECE) is crucial for California’s recovery. Yet even as ECE providers delivered an essential service in caring for and educating young children of essential workers during the pandemic, many providers struggled to meet their own essential needs.

For many ECE providers, the pandemic was the breaking point. Numerous providers who were laid off during the pandemic left the field for good — adding to a staffing shortage at ECE facilities that predated the pandemic.

“It’s important to uplift that ECE programs were struggling with recruiting and sustaining staff before the pandemic. The pandemic just exacerbated that,” said Ashley C. Williams, director of California Policy & Educator Engagement Programs at the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

According to NPR, the Department of Labor reports that day care and other child care jobs have declined nationally by 10 percent — or almost 127,000 — since the pandemic started. In Los Angeles County, the shortage of ECE professionals is estimated to be about 34,000.

Meanwhile, parents returning to work after the pandemic are struggling to find affordable child care. According to the Child Care Alliance of Los Angeles, which provides resources for parents and providers, only 75 percent of child care centers and 80 percent of family child care homes in Los Angeles County were open as of July 31.

“It’s important to uplift that ECE programs were struggling with recruiting and sustaining staff before the pandemic. The pandemic just exacerbated that.” – Ashley C. Williams, Director of California Policy & Educator Engagement Programs at the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment.

“Parents, especially those that need access to subsidized child care, continue to struggle in finding child care,” said First 5 LA Senior Policy Strategist Ofelia Medina. “Overall, need outnumbers the availability of child care spaces, especially for infants and toddlers.”

WHY ARE PROVIDERS QUITTING?

News reports abound about a child care teacher shortage, as providers quit over low pay and other work inequities.

“There are many reasons we are seeing a shortage of early educators, but probably the most impactful and ongoing issue is low compensation in the field,” said First 5 LA ECE Program Officer Jaime Kalenik.

For example:

- The average annual income for a child care provider in Los Angeles County is $27,960. This is not a living wage, especially as many providers end up paying out of pocket for work-related expenses.

- Early educators with a bachelor’s degree are paid 38 percent less than TK-8 teachers;

- Eighty-five percent of ECE providers do not have health insurance

- Early childhood teachers have a poverty rate of 17 percent, nearly seven times higher than K-8 teachers

With such conditions, turnover is not new in the ECE field.

According to a September report on the economics of child care supply by the U.S. Treasury Department, an estimated 26 to 40 percent of the national workforce leave their job each year. Surveys of ECE providers report high levels of burnout and stress.

The pandemic placed an even greater hardship upon ECE providers, according to the University of Oregon RAPID-EC Child Care Provider Survey. This can be seen particularly in the areas of food insecurity, economic hardship and work schedule uncertainty — all which impact providers’ emotional well-being.

The data, released in September, revealed that:

- Twenty-nine percent of providers are experiencing hunger

- One in three providers are experiencing difficulty paying for at least one basic need (food, housing, utilities) during the pandemic

- Fifteen percent of providers cannot afford to pay their rent or mortgage, while 16 percent cannot afford to pay utilities

- One in four providers report having at least one additional job other than providing child care

- As experiences of material hardship increase, providers are also experiencing increasing emotional distress

This emotional distress began early in the pandemic, when providers were getting back-and-forth guidance from the state on whether they should be open or closed, Williams said. Then there was scrambling to get the proper personal protective equipment (PPE) and cleaning supplies for their family- or center-based programs. Providers who continued working risked catching the coronavirus and transmitting it to their families.

“A lot of people left because they were putting their lives on the line and were not receiving the protection and respect they deserved,” Williams said. “Because people were saying, ‘You are essential’ and treating them like they were dispensable.”

For its part, First 5 LA’s ECE team labored hard during this time to support ECE workers. Working with the L.A. County COVID-19 ECE Response Team, over 1.5 million diapers and other PPE and sanitizing supplies were distributed to ECE workers throughout the county.

THE YO-YO EFFECT

The pandemic led to thousands of ECE workers getting furloughed or permanently laid off, while other workers had their hours drastically cut. And when programs did reopen, they had to shut down again if a positive COVID-19 case appeared.

Williams dubbed this open and closing of child care facilities “the yo-yo effect.”

“I think that’s also why a lot of folks left,” Williams said. “One of my good friends was a preschool director — she was really struggling. When she had to close down because of a COVID exposure, she would ask herself, ‘Do I continue to pay my staff or do I pay their health insurance?’ She lost a lot of staff because of the yo-yoing of the programs.”

This instability in the ECE field exists, experts and providers say, because of the systemic racism and sexism that fosters inequities in a workforce that is predominantly women (97 percent) nationwide and, in California, women of color (70 percent). (See related article here.)

THE STRUGGLE TO FIND STAFF

In California, nearly 4,000 licensed child care centers closed permanently during the pandemic. For those providers who survived and reopened, the struggle to find staff has stymied efforts to enroll more children.

“The shortage of staff has had a great impact on our program,” said Early Childhood Directions Director Laura Benevente at Providence St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica. The private tuition program serves mainly parents who are hospital staff, including doctors, nurses, environmental workers and others.

At the onset of the pandemic, the center closed for two months. For numerous reasons, Benevente said, a substantial number of families decided not to return upon reopening, dropping enrollment from 60 to 25 children. Teachers were furloughed and then let go, ultimately reducing her staff from 25 to 12.

“I do have slots open, but in order for me to fill those slots, I need more teachers,” Benevente said. “I have hired slowly, but that has been a challenge, finding people coming back to work. I think some of the inequalities came to light with this. People are underpaid. People have this COVID fatigue. Burnout is a huge one. I think some people have just decided to not work in early care and education anymore.”

“It is hard to retain and recruit enough providers to meet demand when wages are so low, especially when something like the pandemic is bringing so much pressure and uncertainty to people’s lives,” Kalenik said.

FIRST 5 LA PRIORITIZES ECE PROVIDERS

Over the past year, First 5 LA’s policy and governmental affairs team advocated tirelessly in Sacramento with lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration to advance First 5 LA’s priorities, many of which benefit ECE providers.

These include: raising reimbursement rates, adopting rate reform policy, prioritizing construction and renovation of child care facilities and more. All of these were included in the 2021-22 state budget, as well as the creation of 200,000 new state-subsidized child care spaces over the next five years. Read First 5 LA’s analysis of the 2021-22 state budget for more details.

“We have seen huge successes in terms of child care in the state budget,” Medina said. “A lot of the things we have been fighting for during the last couple of years were put into the state budget this year for child care, in part due to the pandemic.”

This is hopeful news for both child care providers and parents seeking child care.

“Overall, it’s greater stability for the field,” Medina said. “In terms of reimbursement rates, it’s a recognition that, historically, child care providers are women of color in a field that does not pay them adequately. The increase in rates is the first step in acknowledging that.”

“In terms of spaces, we know there continues to be a huge need for child care across the state, particularly for infants and toddlers,” Medina added. “The increase for this year and years moving forward will be a strengthening of the infrastructure in general.”

“First 5 LA continues to advocate at the state level with the ECE Coalition for increased compensation for the early childhood workforce,” Kalenik said. “Additionally, we are working locally with system partners to identify resources available through the traditional workforce development system, to increase business supports for Family Child Care homes, and to increase public will for just compensation for child care workers.”

“We absolutely need higher reimbursement rates. It has to be at the true cost of care,” Williams said. “Fifty-two percent of the child care workforce relies on some form of public assistance. It’s just wrong.”

Sometimes, though, things do turn out right.

After spending nine months selling her clothes, doing facials and working other gigs to survive, Rivera has finally made it back to the early learning classroom. In July, she returned to work with Benevente, her old boss at Early Childhood Directions in Santa Monica.

“At one point, I thought that I might leave the child care field,” Rivera said. “I almost gave up, but I didn’t. I try to be optimistic and positive about things and I knew I was going to come back here eventually. I’m very happy to be back.”

Advice for Parents Struggling to Find Child Care

Child Care Alliance of Los Angeles Executive Director Cristina Alvarado gave this advice for parents seeking early care and education for their child:

IDENTIFY YOUR NEEDS: “Think about the type of child care you are interested in. Think about the hours you need.”

REACH OUT: “Contact one of our resource centers. We have a lot of resources for families if they are not sure about finding child care. Go to our website child care search page and click on the map or type in your city. You can also call us by phone: (323) 274-1380 or (888) 922-4453.”

STAY OPTIMISTIC: “We got through this crazy year and a half, and we will keep getting through it.”