Edith Sanchez was concerned.

Officials wanted to test the soil for lead contamination at one of the preschools she oversaw for a non-profit agency. Potential lead contamination from the closed Exide Technologies recycled battery facility in Vernon had prompted soil testing of approximately 10,000 properties from Boyle Heights to East Los Angeles. The year was 2016.

“Just the thought of children being exposed to lead was concerning,” recalled Sanchez, the child development division director at the International Institute of Los Angeles (IILA), which operates 10 preschools and full-day child care centers located throughout the L.A. County area.

Between 2016 and 2017, two of IILA’s preschools were tested for lead in the soil.

“It took a year to get the results,” Sanchez recalled. “Fortunately, they came back negative. I was relieved.”

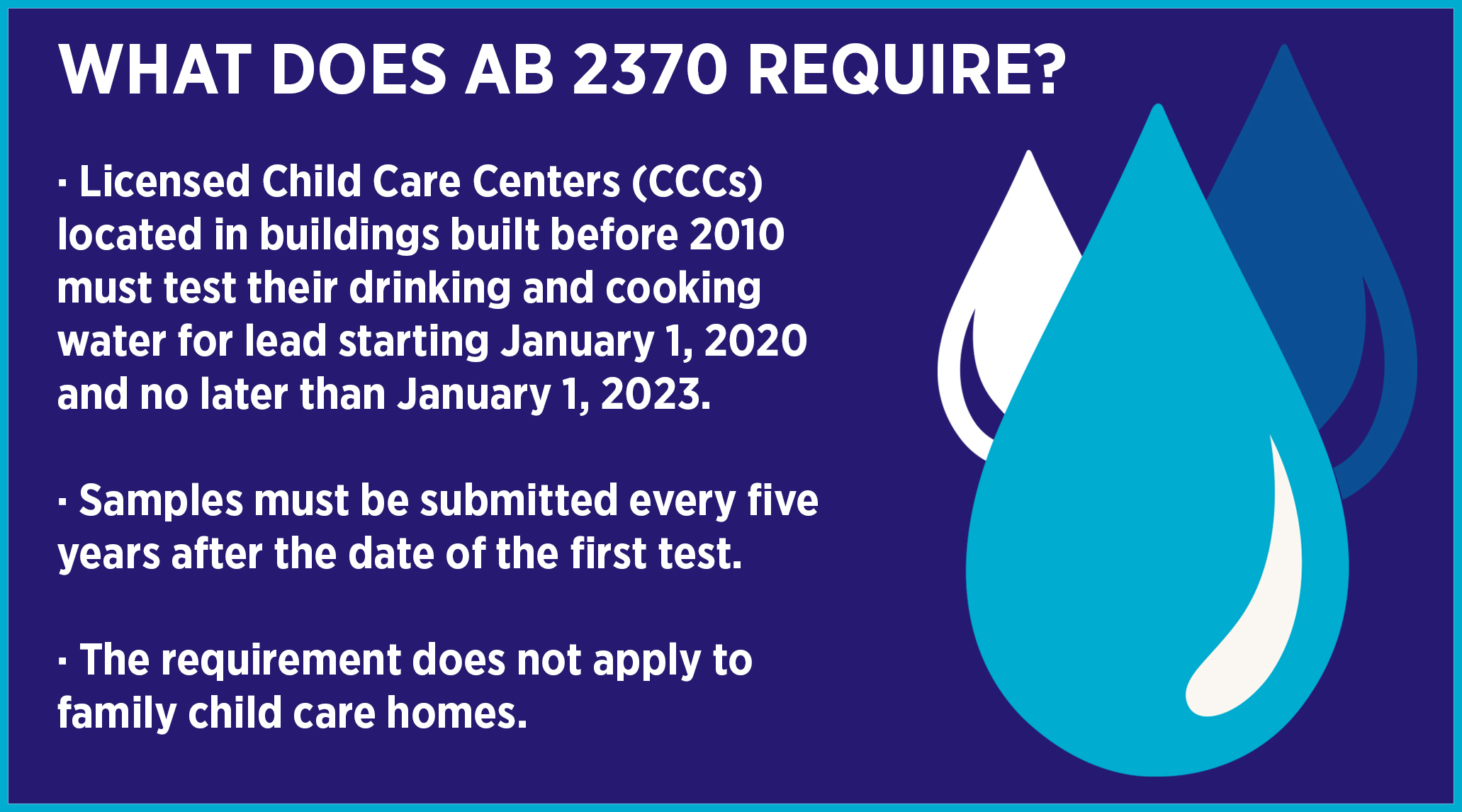

So when she learned that the state had passed a new law that rolls out over three years, requiring testing for lead in drinking and cooking water at each of the 11,000 licensed child care centers in California, Sanchez welcomed the benefit to the public.

“In both instances (of lead testing), the benefit is service to the community,” Sanchez said. “We want the best for the kids. If there is any potential they can be exposed, we want to address that.”

That’s why Sanchez joined about 50 other child care providers from across L.A. County at a January convening to learn about the dangers of lead in water and about the testing requirements established by AB 2370.

Since fall 2019, the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation and First 5 LA have hosted three such convenings, aided in January by the Child Care Alliance of Los Angeles (CCALA).

The convenings’ 135 participants included child care providers, water and environmental advocates, water systems representatives, South Los Angeles community residents, and parents from First 5 LA–supported Best Start Compton/East Compton community partnerships.

The culmination of these convenings is the release of a new report and policy brief this month by Luskin, which recommended that a dedicated funding stream and stakeholder involvement in program design are required to successfully implement AB 2370. The UCLA study details strategies to advance a robust testing and remediation program.

Key to the report were the insights, challenges and concerns raised by the participants at the convenings.

“By 2023, it’s going to be required for all child care centers to test their water, so let’s get ahead of it,” First 5 LA Communities Program Officer Hector Gutierrez said at the January convening at the Salvation Army Siemon Center in South Central Los Angeles. “We want to know what questions are coming up for you and what barriers you are facing. We can elevate these in a report to the state to help provide funding and resources for providers as implementation occurs.”

In California, most of the problem with lead in drinking water comes not from the water system pipes, but from the pipes of property owners, Pierce said.

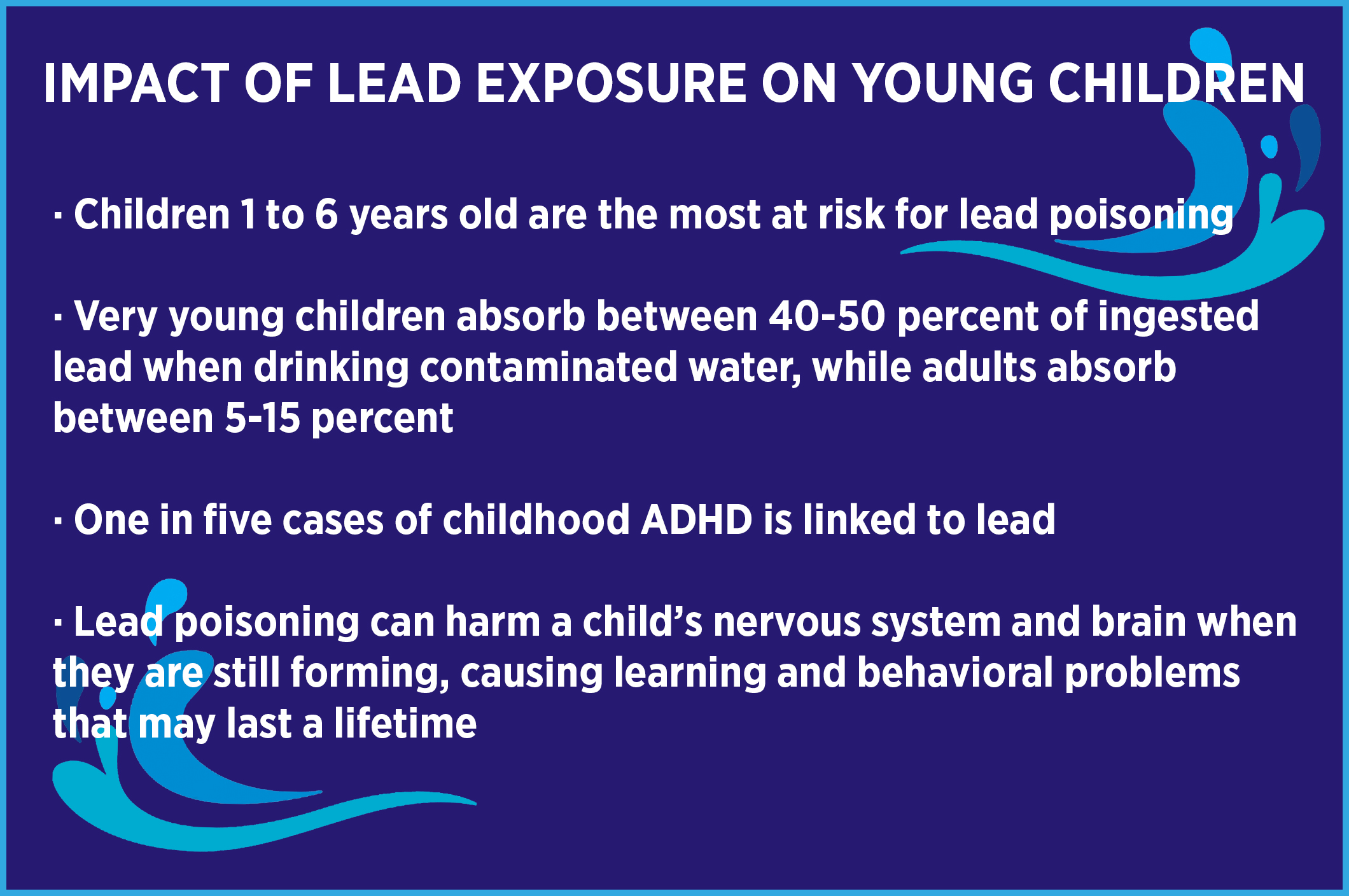

There is no safe level of lead in the body, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The federal government restricts lead in water to 15 parts per billion.

During the lead-in-water crisis in Flint, Michigan, some homes were tested at 27 parts per billion. The highest readings were 13,000 parts per billion.

No parts per billion action level was specified in AB 2370.

As the convenings revealed, many communications around AB 2370 have not reached their intended audience — many childcare providers have not received directives to test their water, and messaging is only available in English and Spanish. At the January convening, the many concerns arising from the lack of specific guidance issued so far by the state prompted a downpour of questions from child care providers.

“How come the family child care homes are not being forced to do this?” asked Maria Rodriguez, a Salvation Army daycare site director.

“I think they want to see how it will work with the child care centers first,” Pierce answered.

“I think they want to see how it will work with the child care centers first,” Pierce answered.

“What’s the average cost of testing?” added Edna Barrera, director of Child Development Services at El Proyecto del Barrio. “If someone comes and says the testing is $800, I want to know if it’s fair or if the tester is trying to take advantage and gouge people.”

“I have seen it cost under $200 for a home and up to $500,” Pierce responded.

“We have to budget for these things, so we can keep our doors open for the community we serve,” said Sanchez, who noted that the Exide soil testing was free.

To help mitigate costs, the state will allocate $5 million in grants for testing and remediation of lead for qualified licensed child care centers (CCCs). The priority for funding will be for 1) CCCs that only operate one facility, 2) those with 50 percent or more children who receive subsidized care, and 3) centers that provide care for newborn children to age 3.

In order to be successful, however, Pierce predicts in the new study that the program will require five to 10 times more funding than the $5 million allocated.

Some questions had no answers.

If the property is rented by a daycare provider, several asked, who is required to pay for the tests and any required fixes? The renter or the landlord?

“We rent and it’s already a struggle to get things done,” Claudia Garcia of the South Central L.A. Ministry Project said at the January convening.

Joyce Robinson could see both sides of the issue. As an early childhood consultant representing many child care centers in South L.A., she has participated in twice-monthly phone calls as part of a child care workgroup on AB 2370 implementation with the state water board and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS), which publishes the written directives for lead testing in child care centers.

Joyce Robinson could see both sides of the issue. As an early childhood consultant representing many child care centers in South L.A., she has participated in twice-monthly phone calls as part of a child care workgroup on AB 2370 implementation with the state water board and the California Department of Social Services (CDSS), which publishes the written directives for lead testing in child care centers.

“Both the state water board — who have never worked with child care — and CDSS are sensitive to the child care providers,” Robinson said. “I think people are trying to make this as easy as possible. They realize this is a big ask, especially for the smaller providers.”

At the same time, she added, “People do have to realize they have three years to get their water tested. They don’t have to panic.”

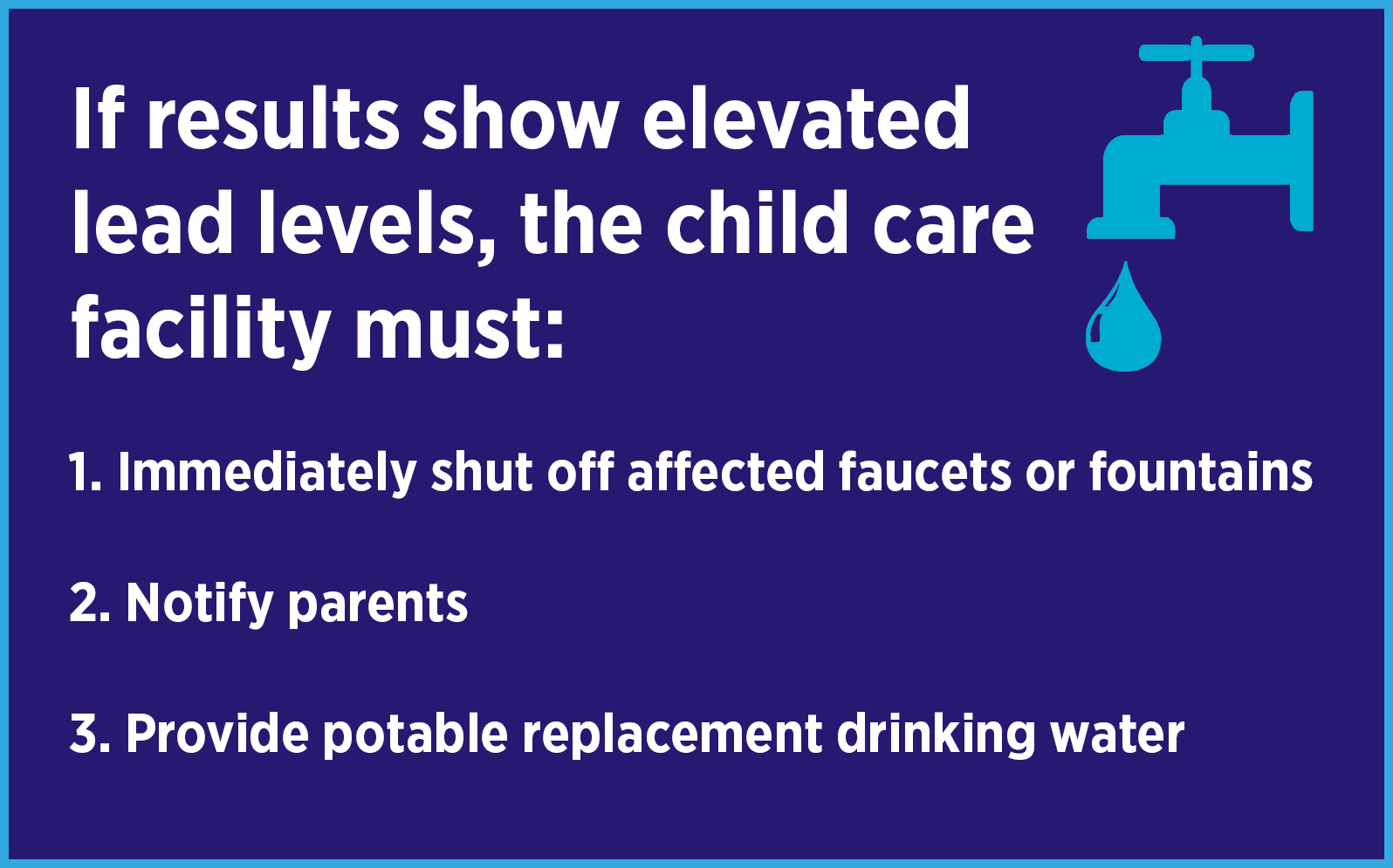

The Child Care Program Office will publish and post written directives outlining the process and requirements that facilities must follow when testing their water for lead, including detailed water sampling instruction and action plans to correct an exceedance of lead. Due to the COVID-19 public health emergency, these directives have been delayed. When complete, the directives will be posted on the CDSS website.

“I’m hopeful that once they release more direction, we’ll have a better sense of what we need to do to prepare,” Sanchez said. “Our goal is to make sure our environments are safe.”

While the desire for safe, clean water for children was agreed upon by all participants, the Luskin report states that a co-design process that includes parents, daycare centers, utilities, and state agencies will result in higher compliance rates and confirm that all centers have their facilities tested in a timely manner.

As far as systems change goes, this is not the end, but just the beginning.

“First 5 LA is looking forward to continuing the conversation around AB 2370 to ensure the environments where children learn and play are safe,” Gutierrez said. “We will continue to use our role as a funder and convener to ensure community voice is elevated as implementation happens in L.A. County.”

This sentiment was echoed at the January convening by Nellie Rios-Parra, director of state preschool and school readiness at Lennox School District: “If we can all work together as one, it makes things easier and we can focus on the kids.”