August 26, 2021

(Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of articles on the ways First 5 LA is working during the pandemic to understand and address the needs of early care and education providers and families of young children in Los Angeles County.)

Like many parents, Asia Simon was both nervous and excited for her 4-year-old son, Carter, to begin his first day of preschool this August.

Like many parents, Asia Simon was both nervous and excited for her 4-year-old son, Carter, to begin his first day of preschool this August.

Unlike many parents, Simon was a former preschool teacher who had experienced the first day of class, literally, for ten years.

But this was a year like no other.

The COVID-19 pandemic had prevented Carter from starting preschool at age 3 in 2020, during which time he either spent the day with Simon at their Compton home as she worked or with his 3-year-old cousin, Chance, at her sister’s home.

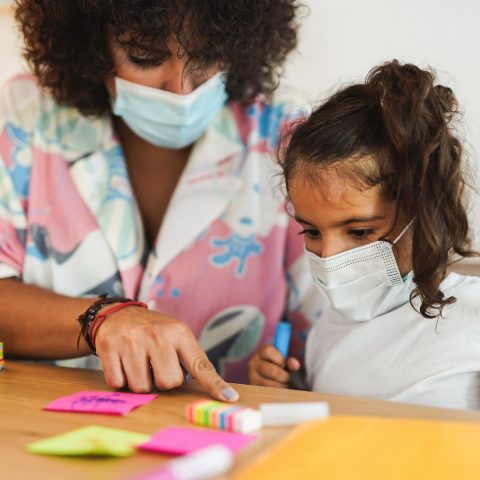

As the start of preschool approached a year later, Simon wondered about the impact of COVID-19: How would Carter feel being dropped off outside of school instead of being joined by his mom in the classroom to help with the transition? How effectively would children socially distance themselves? How would wearing a mask affect his — and his teacher’s — ability to read facial cues? What if teachers or other children get sick? How safe would he be from COVID-19? How would Carter interact in a group setting after more than a year of limited exposure to other kids?

“I’m excited because, as a former preschool teacher myself, I understand the importance of preschool,” Simon said in early August. “I’m nervous because of COVID-19. Even still to this day, I’m going back and forth on whether or not I’m making the right decision for him to go to school.”

Two weeks later, on the first day of class, Simon parked outside the preschool in the early morning. She told Carter she would pick him up before naptime. As she watched, Carter took the hand of his teacher and walked away.

“I struggled a little bit,” she recalled. “I drove to a gas station and cried.”

SOCIO-EMOTIONAL CHALLENGE IS TOP CONCERN

While tears normally accompany watching our children grow up, there is nothing normal about the challenges facing those children entering early learning classrooms during the pandemic.

As a result of academic disruptions caused by COVID-19, an abundance of evidence is revealing that, across the nation, young children will need foundational skills in their return to early care and education environments. Among these, one study revealed that declines in academic and socio-emotional skills are among the greatest challenges faced by young learners — and their teachers — returning to the classroom.

As a result of academic disruptions caused by COVID-19, an abundance of evidence is revealing that, across the nation, young children will need foundational skills in their return to early care and education environments. Among these, one study revealed that declines in academic and socio-emotional skills are among the greatest challenges faced by young learners — and their teachers — returning to the classroom.

One poll released earlier this year revealed that 74 percent of California parents with children birth to age 5 are worried that their child’s education and development will suffer as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In that same poll, parents of young children also worried about their child’s social development, with nearly three-quarters (73 percent) agreeing they worry about their child’s ability to socialize with other children.

In Los Angeles County, First 5 LA is working on a number of ways to understand and address the needs of ECE professionals, young children and their families during the pandemic.

In April, First 5 LA, Child 360 and Early Edge California released a report highlighting the COVID-19 experiences of nearly 600 local ECE professionals, collected in fall 2020 through an online survey and focus groups. The report noted that, as children return to in-person learning, “it is likely that teachers will need additional support to serve children who have not benefited from socio-emotional learning opportunities or instruction during the pandemic.”

In the same survey, providers offering in-person care and distance learning during the pandemic were asked to identify the concerns they had for children in their programs. The concern that was most frequently selected from the provided list was that “children do not have enough social interaction with their peers.” ECE providers stated that physical distancing and some other COVID-related protocols made it more difficult for children to develop critical social-emotional skills.

As one provider explained, “Everything children do is through social interaction. They learn … language development [through social interaction]. They learn to share. They learn to do their numbers by singing … So everything is social for children. That’s how they develop — They develop cognitively, emotionally.”

The pandemic adversely limited social interaction for children in many ways. Playgrounds closed for months. Enrollment varied dramatically at preschools and child care providers alike as parents decided whether to pull their children out. Many early learning programs went virtual to enable children to learn on home computers, while others continued with in-person classes that might have only a handful of students.

“In one class, it was just one child and one teacher,” said Laurel Parker, the preschool director at Norwalk La Mirada School District, who is in charge of 11 pre-K sites with 1,013 kids when fully enrolled.

As the pandemic continues, L.A. County experts in early education shared similar experiences and concerns about socio-emotional challenges facing young children — and their teachers — as in-person enrollment in early learning expands this summer and fall.

Angela Capone, the vice president of early education at Para Los Niňos, oversees seven Head Start and Early Head Start preschools. During the year, she saw sporadic in-person enrollment and emerging socio-emotional challenges.

“One of the biggest things we’ve noticed is we have so many more children who did not have a preschool experience,” Capone said. “So, while they might have started when they turned 3, COVID-19 was alive and thriving. So they didn’t go to preschool. For those children, many of them had never had the opportunity to develop social skills. What we have noticed is that for some children, it’s challenging just learning to be part of a group.”

“We are seeing children that have less patience, Capone said. “I don’t know how it will fully unfold. But we are starting with the assumption that many of our children have suffered trauma over the last 18 months.” – Angela Capone, vice president of early education at Para Los Niňos

Capone noted that some children have shown delays in social engagement with peers. She has also seen some language delays. And she guesses there will be some cognitive delays. “The way to combat that is not to focus on colors and numbers,” she said, “but to support emotional and social skills.”

“The largest challenge I see is socio-emotional — how to interact in social setting — learning how to take turns, ask and answer questions, share, resolve conflict,” said Deborah Lawrence, the child development administrator at Rosemead School District. “The child has to have those skills in place in order to learn. The child has to know how to interact with others and how to regulate themselves.”

Studies show that preschool children who can self-regulate their emotions are often better prepared for school and life. However, employing emotional self-regulation skills may be more challenging during the pandemic for some children.

“We are seeing children that have less patience, Capone said. “I don’t know how it will fully unfold. But we are starting with the assumption that many of our children have suffered trauma over the last 18 months.”

TRAUMA, TYKES & TEACHERS

“In our community of Norwalk, there were families that were hit really hard by COVID-19 and had multiple family members die of COVID-19,” Parker said. “I can name a family with a preschooler where they lost an aunt and a grandparent. I have an employee who lost her maternal grandmother and her father. The kids are young and that will definitely impact them in some way. That’s the part that we really don’t know the full scope of yet.”

“In our community of Norwalk, there were families that were hit really hard by COVID-19 and had multiple family members die of COVID-19,” Parker said. “I can name a family with a preschooler where they lost an aunt and a grandparent. I have an employee who lost her maternal grandmother and her father. The kids are young and that will definitely impact them in some way. That’s the part that we really don’t know the full scope of yet.”

“During the height of the pandemic, we know our parents lost their jobs, had to live with friends, aunts parents, grandparents,” Capone added. “The stability of the family was not pleasant for children. We had more homelessness during the pandemic. A stressed parent did not have the capacity to be emotionally available for their child.”

Since some children struggle to regulate their emotions without the support of a teacher, early learning educators and providers are utilizing trauma-informed and socio-emotional approaches that increase a child’s capacity to regulate their emotions. But what about teachers who need help?

“There is a push to address mental health services for providers, because so much of child development is about relationships. A provider who is understandably struggling may not be fully present in those relationships.” – First 5 LA Early Care and Education Program Officer Jaime Kalenik

“It’s not just what COVID-19 did to the children, it’s also about how it impacted teachers,” Capone said. Just like kids had unstable working environments, teachers had unstable working environments. Working with kids online, working with parents and with their children, working with three kids, then five kids. We were open and then closed. We had 84 instances where we closed classrooms or schools, or kids who would not come to school because they might have been exposed for COVID or tested positive for COVID. The fear of what COVID could bring greatly impacted our teachers.”

A number of school districts have hired more preschool educators and stepped up their mental health services for children, teachers and families alike, adding counselors who provided virtual family sessions. In the classroom, they observe and ask teachers, “What do you need?”

“We boosted the number of mental health consultants from two to three last year — did one-to-one therapy, support groups. They were busy and were doing tons of appointments. The need was high. That was something very different,” Parker said.

“There is a push to address mental health services for providers, because so much of child development is about relationships,” said First 5 LA Early Care and Education Program Officer Jaime Kalenik. “A provider who is understandably struggling may not be fully present in those relationships.”

COACHING & TRAINING TO THE RESCUE

Since the pandemic’s emergence in spring 2020, First 5 LA’s ECE Team has utilized a “systems-thinking” approach and its experience as a convener to help guide the county ECE system over the mountain of challenges caused by COVID-19. As part of this effort, the ECE Team blazed a path with county ECE partners to help create the Los Angeles County Early Care and Education COVID-19 Response Team.

Even before the pandemic, First 5 LA had backed a key support for ECE providers by providing funds and thought partnership for Quality Start Los Angeles, or QSLA, which empowers early learning providers to build upon and improve the quality of care they provide to children birth to age 5. This is done through professional development, specialized trainings, individualized coaching, and access to cutting-edge resources and funding opportunities. QSLA also helps families understand what makes an early learning program effective and how to find the right program for their child.

Even before the pandemic, First 5 LA had backed a key support for ECE providers by providing funds and thought partnership for Quality Start Los Angeles, or QSLA, which empowers early learning providers to build upon and improve the quality of care they provide to children birth to age 5. This is done through professional development, specialized trainings, individualized coaching, and access to cutting-edge resources and funding opportunities. QSLA also helps families understand what makes an early learning program effective and how to find the right program for their child.

QSLA pivoted from in-person activities to online coaching, trainings, live online events and hosted webinars, including partnering with Sesame Street in Communities to help providers learn more about trauma-informed care. Additionally, QSLA offered providers a free socio-emotional kit for preschoolers.

“Immediately, when the pandemic occurred, we were able to offer online learning to all of our providers in QSLA so they could access professional development courses,” said Heather Harris, the director of provider operations at Child 360 and a QSLA coaching co-chair.

In the realm of socio-emotional development, one of the training tools provided by QSLA allows child care providers to listen to children, ask open-ended questions about their feelings and teach them how to express themselves, said Zenaida Meza, a QSLA professional development and coaching manager who works at Child Care Alliance of Los Angeles.

QSLA also offered communities of practice, Meza said, where ECE providers can share what they have learned during the pandemic.

“No one has ever gone through this before. We acknowledge the teachers are the experts,” Meza said. “They are the ones who kept their doors open, did virtual learning. They talk about strategies they tried. It’s a different solution where we bring providers together to share their experiences rather than come forward like we are the experts.”

During the pandemic, the demand for QSLA trainings, tools and coaching grew. Said Harris: “We started with 550 providers prior to the pandemic. We have almost 600 providers in the QSLA network just through Child 360 now.”

“We’ve found that a lot of providers still really wanted the supports QSLA offered even with all the added stresses of the pandemic,” said First 5 LA ECE Senior Program Officer Kevin Dieterle. “Having concrete professional supports to help guide providers during these really uncertain times was something they’ve said they really appreciated.”

“We’ve found that a lot of providers still really wanted the supports QSLA offered even with all the added stresses of the pandemic,” said First 5 LA ECE Senior Program Officer Kevin Dieterle. “Having concrete professional supports to help guide providers during these really uncertain times was something they’ve said they really appreciated.”

“The coaching was helpful,” agreed Parker, whose teachers were observed during Zoom sessions rather than in person. “They were still looking at how teachers were providing instruction. They were checking all the things we want teachers to do in the classrooms. They would meet and review with them and set goals. I’m very impressed with the work QSLA does, even in a pandemic.”

QSLA coaches came back with similar concerns from their ECE providers, as expressed elsewhere. Said Harris: “Teachers are mainly concerned about socio-emotional health, needing mental health resources and strategies for challenging behavior.”

Even as she wondered how Carter would interact with his peers and teachers during his first day at preschool, Simon was learning that teacher-child interaction was the most coached topic at QSLA during the pandemic. That’s because she works as a program supervisor for Child 360, where she supervises QSLA coaches.

Simon also learned that the QSLA switch to virtual coaching has other benefits for early learning providers.

“Before the pandemic, I would have the opportunity as a coach to shadow the teacher in person,” Simon said. “Now teachers upload a recording of an activity they do with their kids. Coaches review the video and make comments. Teachers have an opportunity to review the comments as they see themselves with the kids. It’s actually shown to be quite helpful. Through the pandemic, when coaching virtually, teachers have more time to be reflective.”

Learning the needs of early care and education providers continues to be a priority for First 5 LA in the future.

“The other thing First 5 LA is doing this year is conducting a landscape analysis of home-based child care — encompassing licensed family child care homes and license-exempt family friend and neighbor (FFN) care, such as a grandparent or uncle or aunt who cares for the child,” Kalenik said. “Part of that research is going to ask these providers, ‘What do you need?’ Through this work, we’re going to be able to see the issues providers are facing and will base our strategies on their input, with them at the table.”

A GOOD CHOICE

Like many ECE professionals wondering about pandemic impacts on early learners, Lawrence says providers and teachers “don’t know what we’re going to get when kids come through the door. I think we are going to have our work cut out for us in the fall.”

But there is help, from QSLA coaching and training to sharing experiences in the classroom, as in this story from the First 5 LA/Child 360/Early Edge report. Asked to share creative ways in which they helped children feel socially and emotionally connected in the classroom, one provider noted, “I have a really cute picture of two children sitting in circle time outside. And their little toes are getting towards each other and touching just so that they could be connected.”

As Simon went about her day after dropping Carter off at preschool, she wondered how he was doing and what kind of social connections her son was making. Then her phone rang. Her son’s teacher sent a photo.

“Carter was pretending to serve ice cream to two other children,” Simon said. “It was great to see. He wanted and was able to engage with other kids.”

More photos came through during the day on an app the teacher used, called Learning Genie: Carter painting. Carter excitedly holding a bug while wearing a mask. Carter eating lunch with his classmates.

Simon was elated. “I’m so excited to see how he is going to develop individually because he has exposure to other kids.”

And then, when Simon came to pick him up, 4-year-old Carter said just what his mom needed to hear.

“I had a good day,” he said. “You made a good choice, mommy.”