As the nation struggles with the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, child care has emerged as a key issue. Advocates say now is the time to seek long-term solutions to a pressing problem that has traditionally received scant attention from policymakers.

“One of the biggest lessons of COVID is how important child care is for the economy,” said First 5 LA Senior Policy Strategist Ofelia Medina at the webinar, “The New Normal: Effective Business Engagement on Child Care Issues.” The panel discussion was held earlier this month by First 5 LA and Public Private Strategies, a Washington, D.C. firm that focuses on bringing together business and government to find solutions to societal issues.

Panelists discussed the urgent need for child care as a means to boost economic recovery efforts during the pandemic, as well as the need to work with the business community and legislators to find solutions to an issue that primarily affects working women and low-wage workers.

“We are in a crisis situation when it comes to child care,” said First 5 LA Commissioner Marlene Zepeda. “We need active engagement by the business community.”

Recent research by the National Association for the Education of Young Children found that the country will lose about half of its licensed child care slots by year–end — nearly 4.5 million spots — unless providers receive additional resources. In a survey of 5,000 child care providers across the nation, the association found that two-thirds are running at substantially reduced capacity while facing extra costs for sanitation, staff, and personal protective equipment. And while 18 percent of licensed child care center providers remain closed, the majority of home-based care providers have remained open during the crisis, despite the economic burden. Supporting the unique needs of these providers will be essential in rebuilding a resilient ECE system.

“How are we going to get money into the supply side of these businesses for the next year or so?” said Linda Smith, director of the Early Childhood Development Initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C. think tank.

The pandemic has highlighted what Smith called the “very fragile” state of child care prior to COVID-19. The industry faces high overhead costs to comply with health and safety regulations, which leads to unaffordable prices for working families and low wages for child care employees that, in turn, drives high turnover and a scarcity of staffers. “When it costs more to produce a product than consumers can pay, that leads to a poorly paid workforce and a supply shortage,” Smith said. “It’s a broken business model.”

California State Senator Lena A. Gonzalez (D-Long Beach)

California State Senator Lena A. Gonzalez (D-Long Beach), who chairs the Senate’s Special Committee on Pandemic Emergency Response, said the shortage of affordable child care primarily affects working women, particularly low-wage workers, and during the pandemic, those in “essential” jobs, including healthcare, public safety and support systems such as supermarkets. Employees in small businesses are also particularly affected as these companies are much less likely to provide any type of child care resource or leave policy, she said.

“Child care,” Gonzalez emphasized, “is an equity issue.”

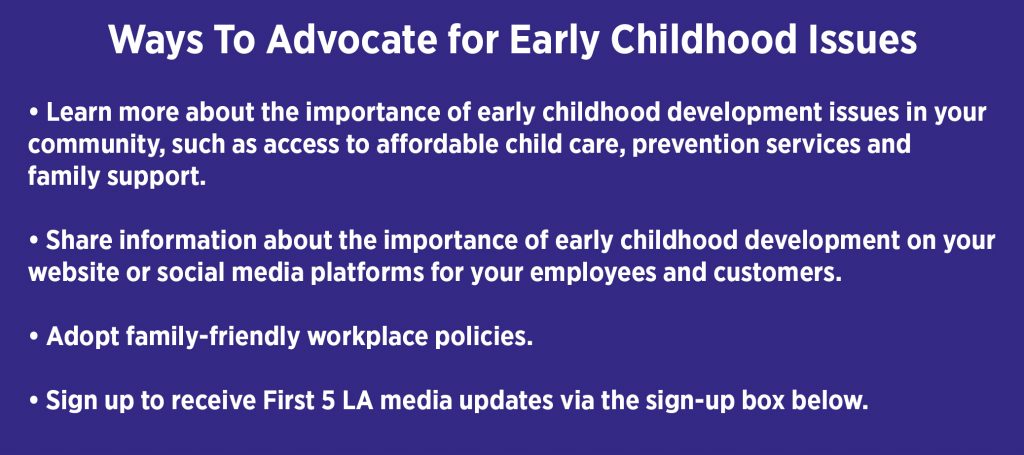

More needs to be done to create awareness among business owners of how child care benefits their bottom line through increased employee productivity and reduced turnover — even if it’s as simple as having a backup staffing plan in case a worker has to stay home with a sick child, Gonzalez said. “The return on investment is huge for companies,” she said. “There needs to be a better dialogue.”

She noted that, in the past, she had found business owners reluctant to support family issues such as legislation mandating 12 weeks of unpaid family leave for employees. “Although there was no cost to the employer, a lot of the business community did not support this. It was astonishing to me,” she said.

Jessica Lall, President and CEO of the Central City Association of Los Angeles that represents the commercial and residential interests of downtown Los Angeles, said the association has made child care the top focus of its advocacy efforts as it is vital to developing downtown into a thriving, family-friendly residential neighborhood. The area currently has about 80,000 residents and is projected to reach 250,000 by 2040. “We’re not going to be able to sustain downtown’s growth as a community without an early childhood care option,” Lall said.

Panelists said they are working on solutions with various levels of government. The California Legislative Women’s Caucus is working on proposals to finance more slots for subsidized child care in upcoming state budget talks, Gonzalez said. And Lall reported that, in addition to supporting Los Angeles City Council President Nury Martinez’s proposal to provide child care vouchers, the Central City Association recently published a white paper and formed a task force to advance ways to expand child care options.

At the federal level, both houses of Congress have passed separate measures to channel funding to the child care industry, but neither bill has been approved by both houses. The House of Representatives proposed $60 billion in direct funding to child care providers in two bills, while the Senate planned earmarking $15 billion for child care grants.

Panelists said more must be done to stabilize child care supply for the long term. Mandating paid leave for new parents, providing aid to small businesses so they can provide family leave, and implementing subsidized models — such as one employed by the armed forces, where parents and the military share the child care cost — are all avenues to easing the burden on working parents, Smith said.

“As a nation, we’re going to have to come to terms with child care and do better for young families,” she said.