October 28, 2021 | 5 Minute Read

At a recent national family home child care provider conference in New Orleans, a speaker invited the attendees from the field to stand up and shout out what issues needed to be addressed in child care.

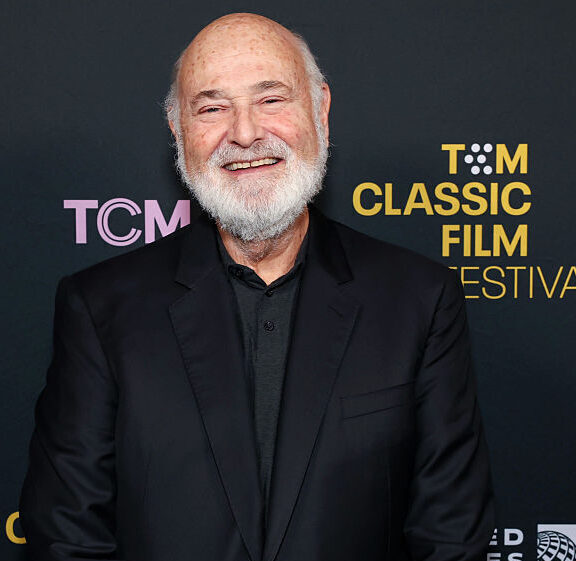

Tonia McMillian

Several attendees drew applause when they shouted out issues involving the business of running a family child care. Then Tonia McMillian, owner of Bellflower-based Kiddie Depot Family Child Care, stood up.

“Systemic racism and sexism,’” McMillian shouted to her colleagues.

The reaction?

You could have heard a diaper pin drop.

“It was quiet,” McMillian recalled. “Nobody wants to hear about it or have a conversation about it.”

From child care conferences to the state capitol, addressing the age-old issue of systemic racism and sexism in child care is uncomfortable at best. At worst, it leads to the perpetuation of inequities experienced by women of color who make up 40 percent of child care workers nationwide and 70 percent of those in California.

Among these inequities:

- According to the Advancement Project, the early learning workforce made approximately $14.38 per hour nationally. Yet Black women made $12.98 and Latinas only $10.61 hourly

- African American and Latino early educators are more likely to be in the lowest-paying jobs nationwide, such as assistant teachers

- Black early educators experience poverty at as much as double the rates of their white peers

According to a study released in August by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) at UC Berkeley: “While nearly all early educators are poorly paid, there are disparities driven by a combination of public policy, funding, and systemic racism. The result is a system in which Black educators and those who work with the youngest children are systematically paid the least.”

Ashley C. Williams, Director of California Policy & Educator Engagement Programs at CSCCE

“Black women are earning 78 cents less on the hour than their white peers for doing the same work,” said Ashley C. Williams, director of California Policy & Educator Engagement Programs at CSCCE. “Looking at these figures are examples of how racism and sexism are present in the ECE sector.”

“If this was a male-dominated field, we probably wouldn’t be having this conversation,” McMillian said. “Men don’t put up with this.”

Then there is the disparity in job roles.

In California, for example, 69 percent of white staff are teachers in child care centers. In contrast, only 60 percent of African American staff and 50 percent of Hispanic staff are teachers at child care centers, according to the CSCCE.

“Because of the low wages, you would think that these folks don’t have the education, but that’s not the case,” Williams said. “Two-thirds of center-based workers have BA degrees or higher. I think that’s a prime example of racism and sexism — they are teachers doing this work, yet they are paid poverty wages.”

According to a September U.S. Treasury Report, since the vast majority of the workers are women and disproportionately women of color, the sector likely benefits from existing discrimination in labor markets. This does not suggest that child care providers are at fault but is an indication of just how untenable the economics of the industry are, the report states.

Ultimately, Williams said, systemic racism and gender oppression “compromise the early education that children and families receive.”

So where did this systemic racism and sexism originate?

“Historically, this has been women’s work, with roots steeped in slavery,” said McMillian, a member of California’s Early Childhood Council. “African American women and Latinas have been historically limited to domestic work, including caring for rich people’s kids. That has carried into this field. People may not want to admit it. But that’s where some of the implicit bias lies, and it’s very, very real.”

The ongoing inequities have resulted in an industrywide child care provider shortage that worsened during the pandemic, when nearly 4,000 statewide child care closures put thousands of ECE providers out of work. Even as child care facilities slowly began to reopen, many staff and teachers have not returned.

“The pandemic was the breaking point,” McMillian said.

“Systemic racism drives the child care crisis by being founded as a service carried on the backs of women of color receiving little to no pay,” said First 5 LA Senior Policy Strategist Ofelia Medina.

For McMillian, elevating the issue is the first step in eliminating implicit bias. She took her case to lawmakers in Sacramento.

“I had to educate lawmakers that I was a businesswoman and not a babysitter,” she said. “As I started talking about my business, the respect came.”

First 5 LA has long worked with lawmakers to advocate for higher reimbursement rates — a key step to reducing inequities in the field — as well as provide other supports for early learning providers. This effort came to fruition in this year’s state budget.

But more needs to be done to combat implicit bias and systemic sexism and racism in the field. And it needs to start sooner.

Just ask Eva Hoffman-Murry.

Hoffman-Murry, a Black owner of Kiddie Kare, a licensed family child care business in Bellflower, said she recently had two Caucasian parents check out her facility. They brought their two children, a 2-year-old girl and a 4-year-old boy.

“There are societal attitudes towards the work that make it unappreciated and societal racism that make it uncomfortable.” – Stephanie Orozco, Former Preschool Teacher

Eva Hoffman-Murry

“The mom was super cool and the dad was like, ‘mmm-hmm.’ The children held the dad’s hand the entire time,” Hoffman-Murry recalled. “When I bent down to say hello, the girl screamed. You can tell as a person of color that they have not been around Black people.”

Just then, another parent who was not Black walked in, said ‘Hi’ and waved.

“The dad and the babies both waved,” Hoffman-Murry recalled. “The mom was like, ‘I’m so sorry. They just woke up from a nap.’ Give me a break. It’s the society we live in.”

Stephanie Orozco understands.

“There are societal attitudes towards the work that make it unappreciated and societal racism that make it uncomfortable,” said Orozco, a former preschool teacher.

Orozco recently joined First 5 LA as a program officer on the ECE team, where she hopes to elevate the ECE provider experience through the team’s creation of a provider advisory group and by convening local providers to discuss ground-level issues.

Openness and honesty, she said, are the first steps in addressing issues such as systemic racism and sexism in the ECE field.

“I think it starts with everybody involved taking a look at their internal biases, at their policies, in the way they are creating pay scales and in the demographics of the people in power who are making decisions that impact child care workers,” Orozco said. “And anyone who interacts in child care system should examine their own attitudes toward child care staff and the system overall.”