March 30, 2022

During his recent State of the Union address, President Joe Biden promised to cut the cost of child care to help “millions of women who left the workforce during the pandemic because they couldn’t afford child care.” His statement shined a light on the mass exodus of women from the workplace because of the COVID-19 pandemic — what’s been dubbed a “She-cession” — and the stark reality that, despite great strides in gender equality, women are still expected to care for children when things go wrong.

What many people, including Biden himself, may not realize is that the U.S. child care system was not — at least initially — built to promote women in the workforce. Rather, organized child care emerged as a temporary or emergency response for those women who had to work out of necessity. But as the number of women in the workforce grew over time, the ensuing social debate over whether women should work at all served to hobble progress toward accessible child care for decades. Although attitudes have largely changed, the scattershot and unevenly woven state of today’s child care system — reflecting the tension between modern-day sensibilities and the antiquated but persistent notion that “a woman’s place is in the home” — remains to this day.

For Women’s History Month, we are looking back at the origins of child care in the U.S., from its beginnings as a Quaker-led philanthropic effort to its current place in the government sphere. We’ll also explore how competing priorities related to quality, access and need have slowed movement toward a comprehensive child care system in the U.S., leaving mothers to pick up the slack.

While women have found ways to work while raising young children since the dawn of civilization, one of the first documented cases of organized child care enabling women to work was the Philadelphia House of Industry. Founded in 1798 by female Quaker philanthropists, the House nursery was adjacent to a spinning room that employed widowed women. The practice for widowed mothers at the time was to break up the family by sending children to orphanages or indentured servitude, and the mothers to almshouses. However, the House of Industry nursery allowed mothers and children to stay together.

While women have found ways to work while raising young children since the dawn of civilization, one of the first documented cases of organized child care enabling women to work was the Philadelphia House of Industry. Founded in 1798 by female Quaker philanthropists, the House nursery was adjacent to a spinning room that employed widowed women. The practice for widowed mothers at the time was to break up the family by sending children to orphanages or indentured servitude, and the mothers to almshouses. However, the House of Industry nursery allowed mothers and children to stay together.

The first formal child care institution was New York City’s Nursery for the Children of Poor Women, founded in 1854. Serving as a model for day nurseries throughout the nation, this day nursery was established to prevent low-income mothers from becoming dependent on charity or prostitution and served as a model for day nurseries throughout the nation. This initial association between maternal poverty and child care, however, was one of the first obstacles in building an intentional system to support women in the workplace.

As America entered the Progressive Era of the 20th Century more eyes were on child care. Kicking off reform efforts was the Model Day Nursery at the Chicago World’s Fair — a clean, bright and cheery child care exhibit set up by wealthy philanthropist Josephine Jewell Dodge. The nursery’s professional feel stood in contrast to the dingy stereotype of day nurseries and inspired a rise in philanthropic support. Despite these improvements, however, the philosophy that child care should only be temporarily available for mothers in dire straits persisted. So when Dodge founded the National Federation of Day Nurseries (NFDN), the first nationwide organization devoted to the issue of child care, she used the platform to promote this belief.

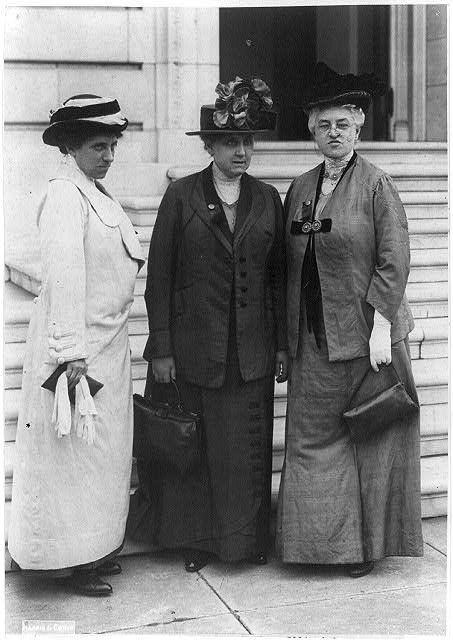

To further deter mothers from working, Progressive-Era leaders like Jane Addams and Julia Lathrop advocated for “mother’s pensions” that would allow mothers to stay at home with their children. By 1930, nearly all states had some form of mother’s pension. However, these pensions were never adequate. So despite their intent and persistent cultural beliefs, mothers continued to enter the workforce. Lathrop went on to head the first U.S. Children’s Bureau and used the powerful seat to advocate for mother’s pensions, despite knowing that child care was inadequate for the rising number of working mothers.

To further deter mothers from working, Progressive-Era leaders like Jane Addams and Julia Lathrop advocated for “mother’s pensions” that would allow mothers to stay at home with their children. By 1930, nearly all states had some form of mother’s pension. However, these pensions were never adequate. So despite their intent and persistent cultural beliefs, mothers continued to enter the workforce. Lathrop went on to head the first U.S. Children’s Bureau and used the powerful seat to advocate for mother’s pensions, despite knowing that child care was inadequate for the rising number of working mothers.

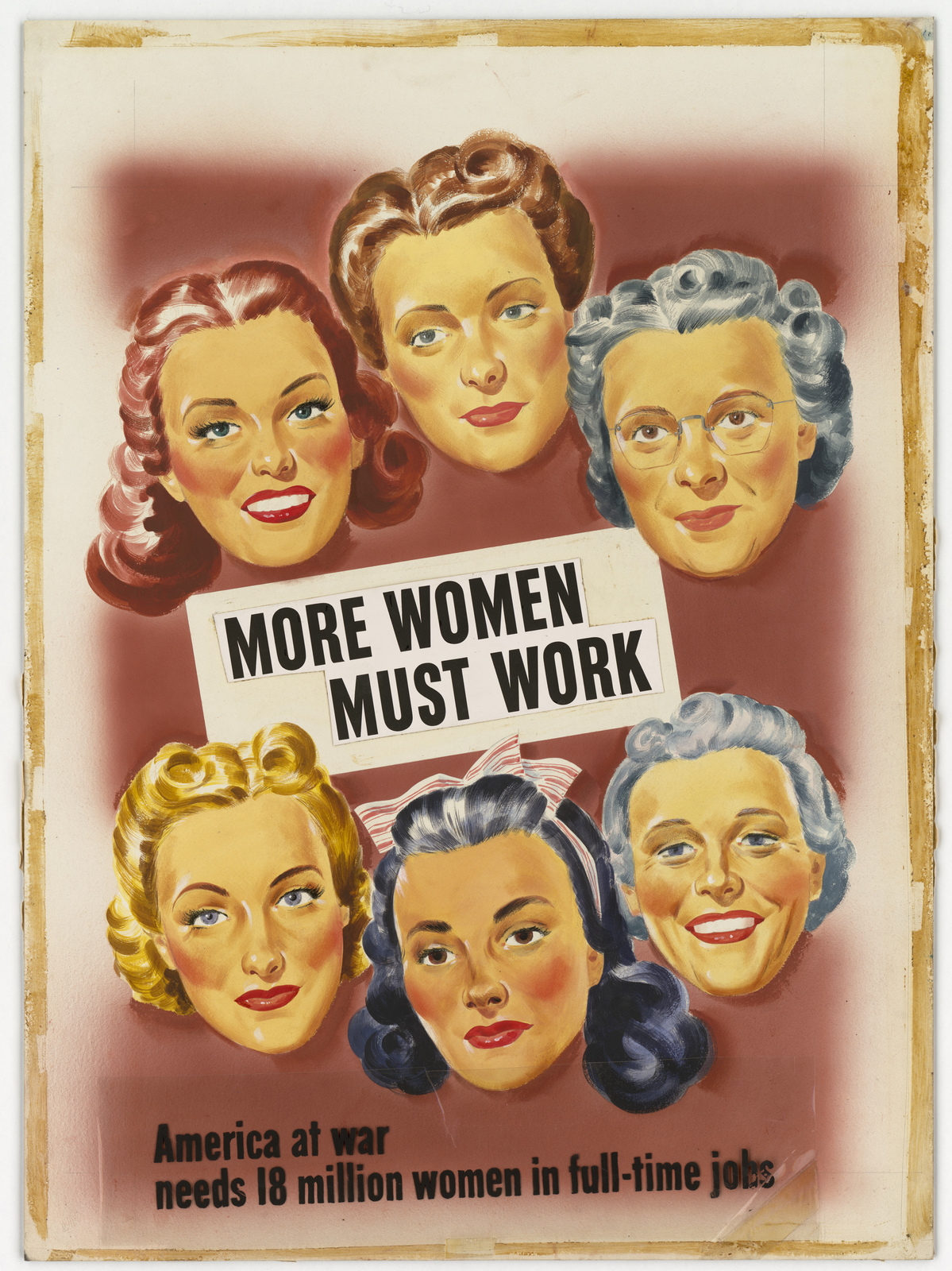

Global calamities such as World War I, the Great Depression, and especially World War II called on more women than ever before to enter the workforce. Throughout these various crises, different factions emerged within the philanthropic sector, academia, and the government sector, all with opinions on how to look after children while a female workforce was meeting the needs of society. And while there are well-documented cases of governmental efforts to support child care during this time, the ongoing jockeying between the splintered factions, coupled with the prevailing social norm that a mother’s primary job is in the home, prevented such efforts from scaling adequately. As a result, many closed down after the crisis at hand passed.

One such example of factions influencing federal support was the New Deal’s Emergency Nursery Schools (ENS) program of the 1930s. Early childhood educators convinced Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration to chose higher-quality nursery schools to meet child care needs instead of day nurseries, which were private institutions established for wealthier families, and fewer existed. The dearth of available Emergency Nursery Schools, even with government funding supporting them, forced mothers to scramble for care. However, the ENS framework did leave behind a model of quality that would continue to be influential.

Another element working against the adoption of government-supported child care at this time was the emergence of psychologically-based theories that pathologized the idea of working mothers and warned that children receiving care outside the home would be corrupted and at risk of becoming delinquent. Such theories proved useful for conservative politicians who, when faced with legislation that would continue child care after World War II, used this pathologizing language to veto the bills.

After WWII, almost a decade went by without federal support for child care. In 1954, the government, finally used the tax system to meet families’ child care needs by providing a tax credit for middle-income families. However, the tax credit was inadequate for the working poor, spurring reformers to establish the Inter-City Committee for Day Care of Children (ICC), which stressed the need to “safeguard children’s welfare,” by making care more widely accessible.

As a result of the ICC’s urging, the federal government hosted the National Conference on the Day Care of Children in November 1960. Although the conference proved successful in promoting the normalization of mothers in the workforce, it did little to garner sufficient political will to form a coherent child care policy. During this time, Congress instead, reinforced the century-old correlation between child care and low-income working women by making federally supported child care available only to those who, without support, would become dependent on public welfare or Aid to Families with Dependent Children. In response to this inadequate support, a coalition of feminists, civil rights activists and early childhood advocates designed the Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971, which would have established a national day care system; however, the bill was ultimately vetoed by President Richard Nixon. The veto reflected a confluence of forces, including a veiled desire to prevent African Americans from having access to adequate child care.

As a result of the ICC’s urging, the federal government hosted the National Conference on the Day Care of Children in November 1960. Although the conference proved successful in promoting the normalization of mothers in the workforce, it did little to garner sufficient political will to form a coherent child care policy. During this time, Congress instead, reinforced the century-old correlation between child care and low-income working women by making federally supported child care available only to those who, without support, would become dependent on public welfare or Aid to Families with Dependent Children. In response to this inadequate support, a coalition of feminists, civil rights activists and early childhood advocates designed the Comprehensive Child Development Act of 1971, which would have established a national day care system; however, the bill was ultimately vetoed by President Richard Nixon. The veto reflected a confluence of forces, including a veiled desire to prevent African Americans from having access to adequate child care.

Throughout the 1980’s, President Ronald Reagan’s conservative policies drastically reduced federal child care support for low-income Americans and instead made sizeable increases to tax incentives for middle- and upper-class Americans, including the Child Tax Credit and subsidies for businesses providing care. These tax incentives served to supercharge the makeshift patchwork of child care options that had grown out of women’s need to find adequate care, including the development of child care center chains, proliferation of family day care and in-home nannies. In essence, the tax incentives allowed the market to decide what care would be available to families, ultimately dividing available care along class lines.

Since these Reagan-era policies, American families have relied on this makeshift patchwork of care, rooted in decades of vacillation around women’s right to work as well as the persistent affiliation of federally funded child care with women in poverty. In recent years, the pandemic effectively crippled child care systems across the nation, prompting mothers at all income levels to leave the workforce so that they could care for their children. This has forced Americans to re-evaluate the role child care plays — not just in women’s lives, but in society at large.

American politicians are again faced with an opportunity to support and implement a system that allows for women’s full participation in the workforce. But will women’s right to work prevail? As of this writing, both Republicans and Democrats agree that child care in the U.S. needs robust support, however, how we go about it continues to stymie progress, and could change at any moment

Sources for this article include:

- Children’s Interests/Mothers’ Rights: The Shaping of America’s Child Care Policy by Sonya Michel, Ph.D., University of Maryland

- The history of child care in the U.S. Social Welfare History Project at Virginia Commonwealth University by Sonya Michel, Ph.D., University of Maryland